2.1. Vectors¶

Vectors are simply 2, 3, or 4 dimension elements. In OpenGL we often use them to specify position, direction, velocity, colour, or a lot more.

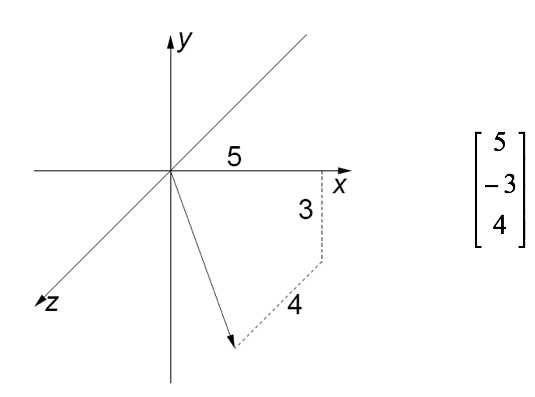

The axes as shown in the image above are the default OpenGL axes. However, it is possible to change them, inverting the Z axes.

2.1.1. Vector operations¶

To add or subtract vectors, simply each of the dimensions together.

The length of a vector is given by the equation \(|V| = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + z^2}\).

To scale a vector (multiply a vector by a scalar), just multiple each of the dimensions by the scalar.

To normalise a vector, divide the vector by its length, like so

2.1.2. Normal vectors¶

Normal vectors can be normalised, but they are not the same thing!

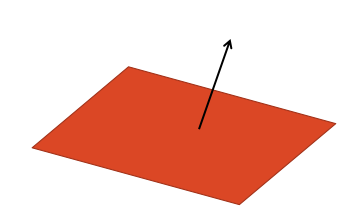

A normal vector specifies the direction which a surface is looking towards.

For example, in a cube you would want the light to shine on the outside of the cube, and not on the inside. What to do is define the normals for each of the vertices of the cube to be facing outwards from the cube. If you made them face inwards, then the cube would be lit on the inside, and would look black on the outside.

The image above shows the normal vector for a plane.

Remember that the normal vector is the direction the plane is looking towards. If we change the normal vector without changing the rotation of the plane, the lighting would change, but it may not look physically realistic.

2.1.3. Dot Product of Two Vectors¶

To calculate the dot product of two vectors, watch the video here.

The dot product can be calculated as:

Or as this:

So therefore it can be useful, if we know the vectors, we can rearrange the equations to calculate the angle between the two vectors.

So, therefore:

A more comprehensive explanation of why that works is here.

2.1.4. Cross Product of Two Vectors¶

To calculate the cross product of two vectors, watch the video here.

The cross product can be calculated as:

Where:

- \(|a|\) is the magnitude (length) of vector \(a\)

- \(|b|\) is the magnitude (length) of vector \(b\)

- \(θ\) is the angle between \(a\) and \(b\)

- \(n`is the unit vector at right angles to both :math:`a\) and \(b\)

So we can re-organise that equation to calculate \(n\).

Thus the cross product can be used along the dot product to calculate a unit vector perpendicular to a plane.

What this is useful for, is to calculate normal vectors of a plane, when we only have points directly on the plane to work with. This will be extremely useful to calculate lighting later on.

A more comprehensive explanation of why that works is here.

2.1.5. Homogeneous Coordinates¶

Homogeneous coordinates are just 3D vectors that instead of 3 dimensions have 4 dimensions. Usually the 4-th coordinate is 1.

This is used for things like translations (we will see soon), and to define whether a vector is simply a direction (w == 0) or a position (w != 0).

Thus the vector (x, y, z, w) corresponds in 3D to (x/w, y/w, z/w).